In SFF Onstage, we’ll be exploring the roots and representations of science fiction and fantasy elements in plays throughout history, focusing of the scripts and literature of the theatre, rather than specific productions or performances.

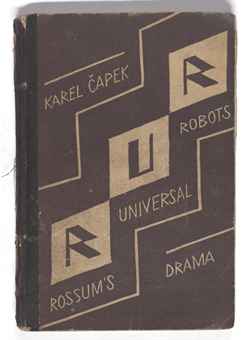

I’ll be totally honest with you: I had never actually heard of, much less read, RUR until I watched Joss Whedon’s kind-of-a-mess-but-totally-underappreciated Dollhouse. In the second season episode “Getting Closer,” Clyde 2.0 explains that the Rossum Corporation took their name from some obscure play. As a playwright who also works for one of the largest regional theaters in the country, this came as a surprise to me. A quick search lead me to Karel Capek’s RUR, or “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” The play had its premiere in Prague in 1921, and allegedly introduced the word “robot” into the vernacular (although words such as “automaton” and “android” had previously been used). It was also the first piece of science fiction television ever broadcast, in a 35-minute made-for-TV adaptation on the BBC in 1938.

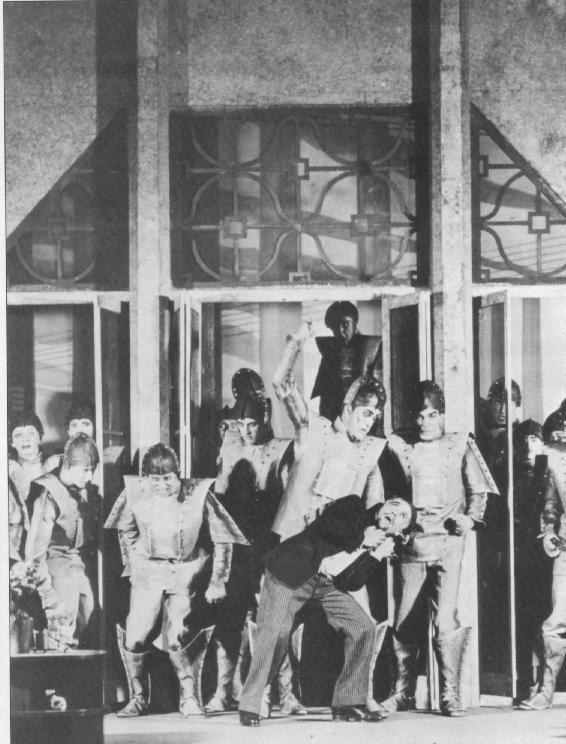

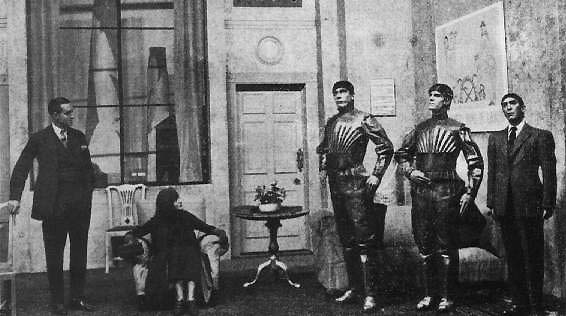

In the original Czech, “robota” refers to forced or serf labor, derived from the root “ran” meaning “slave.” That being said, the “robots” in RUR have more in common with golems or homunculi than the mechanical beings that we typically associate with the word today. In the play, the robots are biological creatures built from raw materials and assembled on a factory line. These robots are virtually indistinguishable from humans other than the fact that they were artificially created and are technically sexless (although they are still gendered). By the start of the play, robots are commonplace throughout the world and have been for about 40 years, providing cheap physical labor for humans.

The entirety of the play is set in the tallest tower of the island headquarters of Rossum’s Universal Robots. The action begins when Helena, a representative of the Humanity League and daughter of a noted industrialist, visits the tower in the hopes of liberating the poor, oppressed robots. Domin, the company’s general manager, is able to convince her that despite their appearances, these robots are not actually people with the same traditional feelings as the rest of us. They are capable of thinking for themselves, but they’re quite content to exist as subservient laborers for the benefit of mankind. Although she accepts this, Helena still remains skeptical, and like all good female protagonists of the early 20th century, immediately falls in love with Domin, I guess because he’s a man and he has money and he tells her. Because what educated and fiercely independent woman wouldn’t immediately fall in love with a wealthy man who loves her and also made his fortune creating less-than-human laborers?

The entirety of the play is set in the tallest tower of the island headquarters of Rossum’s Universal Robots. The action begins when Helena, a representative of the Humanity League and daughter of a noted industrialist, visits the tower in the hopes of liberating the poor, oppressed robots. Domin, the company’s general manager, is able to convince her that despite their appearances, these robots are not actually people with the same traditional feelings as the rest of us. They are capable of thinking for themselves, but they’re quite content to exist as subservient laborers for the benefit of mankind. Although she accepts this, Helena still remains skeptical, and like all good female protagonists of the early 20th century, immediately falls in love with Domin, I guess because he’s a man and he has money and he tells her. Because what educated and fiercely independent woman wouldn’t immediately fall in love with a wealthy man who loves her and also made his fortune creating less-than-human laborers?

But I digress.

The next scene (technically “Act One”) is set 10 years later, and although Helena has remained on the island with Domin, she still can’t shake her maternal instincts, those pesky emotions that keep telling her that these “robots” might actually be human after all. Dr. Gall, Rossum’s resident psychologist, creates several “experimental” robots, with even more human-like features and capabilities—including one that resembles Helena, which is totally not creepy at all. Also, it should be noted that these new robots are, uh, “fully equipped,” if you will. Despite this minor detail, Dr. Gall and the rest of the staff at Rossum continue to insist that these robots are still less than human. Helena, meanwhile, has burned the master “recipe” for the robots, in the hopes that these indentured servants will be set free if Rossum is no longer able to create new robots. By the end of the act, the Soviet Working Class, I mean the robots have risen up against their creators and prepared for revolt, and swiftly slaughter all of their creators at Rossum—with the exception of Alquist, Rossum’s Clerk of Works, whom the robots view as one of their own.

The next scene (technically “Act One”) is set 10 years later, and although Helena has remained on the island with Domin, she still can’t shake her maternal instincts, those pesky emotions that keep telling her that these “robots” might actually be human after all. Dr. Gall, Rossum’s resident psychologist, creates several “experimental” robots, with even more human-like features and capabilities—including one that resembles Helena, which is totally not creepy at all. Also, it should be noted that these new robots are, uh, “fully equipped,” if you will. Despite this minor detail, Dr. Gall and the rest of the staff at Rossum continue to insist that these robots are still less than human. Helena, meanwhile, has burned the master “recipe” for the robots, in the hopes that these indentured servants will be set free if Rossum is no longer able to create new robots. By the end of the act, the Soviet Working Class, I mean the robots have risen up against their creators and prepared for revolt, and swiftly slaughter all of their creators at Rossum—with the exception of Alquist, Rossum’s Clerk of Works, whom the robots view as one of their own.

Once the robots have wiped out their oppressors (aka the entire human race), they charge Alquist with re-discovering the formula for making new robots, in order to perpetuate their race. Soon enough, Alquist realizes that he will have to begin dissecting robots in order to properly study them. But when Dr. Gall’s advanced experimental robots with genitals show emotions and resist the notion of being slaughtered in the name of science—dare I say, when they appear to have fallen in love—Alquist concedes and allows them to live on as the new Adam & Eve, encouraging them to procreate and perpetuate the robot new human race.

The central philosophical idea of the play is whether or not these “robots” are in fact less than human, simply because they were born (or created) under different circumstances. This of course remains a popular theme in more recent stories involving robotics. But in the case of RUR, the question seems to be less about artificial intelligence, and more about issues of class. What’s that? A Czech play written in the early 1900s dealing with labor and class? I know, I know, it sounds absolutely preposterous. I mean, really? The bourgeoisie human creators of Rossum’s Universal Robots viewing their free-thinking Bolsheviks laborers as being “content” in their conditions? And those same Laborers, born into that condition, rising up against the ruling class? That’s crazy talk! Er, maybe not. Either way, it certainly begs the question of whether modern (but not necessarily “Modernist”) interpretations of “robots” have been inspired by the work of Karel Capek in name alone, or if these Marxist-Leninist philosophies are intrinsically linked to the more contemporary explorations of technology and artificial intelligence. I think a case can be made for both sides.

While RUR is not commonly produced today, you will occasionally find theatre companies attempting to bring a modern interpretation to the stage. There was supposedly a Brazilian adaptation in 2010 that used actual robots to play the “robot” roles. If you’re interested in further reading, the entire script is available online for free under a Creative Commons License.

Thom Dunn is a Boston-based writer, musician, homebrewer, and new media artist. He enjoys Oxford commas, metaphysics, and romantic clichés (especially when they involve robots). He firmly believes that Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” is the single worst atrocity committed against mankind. Find out more at thomdunn.net